If you are close to anyone who has been diagnosed with dementia, in particular frontotemporal dementia, also known as Pick’s Disease, this book is an essential read. You will probably already know that Pick’s disease is one of the most serious forms of dementia and affects the front and sides of the brain. Whereas most other forms of dementia tend to come on in later life, Pick’s Disease often strikes those between the age of 45 and 65 and sometimes even earlier than that.

It tends to develop slowly over time and the first signs are that the person affected will start behaving in strange and unexpected ways, which may include disinhibition and socially inappropriate behaviour, symptoms which will gradually become more extreme and challenging as time goes by. This form of dementia also brings about a loss of verbal memory, which will render a person’s speech increasingly unintelligible.

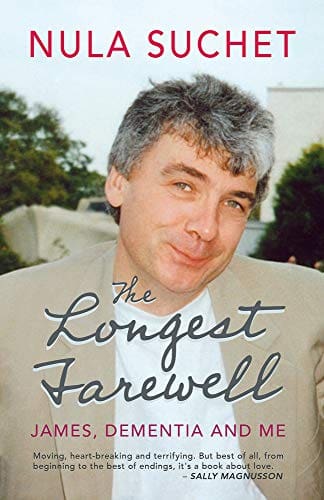

The writer of The Longest Farewell, Nula Black, is married to a successful and gifted filmmaker called James. After many years of happy marriage, Nula begins to notice that James is starting to do funny things and have strange moods. Bearing in mind he is only 57, she initially puts his odd behaviour down to him working too hard and becoming a bit absent-minded. But as she says, “Surely he shouldn’t be losing his keys and glasses quite so often, or leaving his favourite jacket and valuable wrist watch on a film shoot, or his passport on a plane, and why is he forgetting to return important work calls?” Clearly something is not right with him.

Inwardly Nula becomes increasingly alarmed, but nevertheless decides to play things down and try and make allowances for her husband’s increasingly strange behaviour. Finally, after nearly two years of devoted but increasingly frustrating care and support, Nula takes James to see a specialist in Harley Street. After a few cursory tests the specialist comes straight out with his diagnosis: “Dementia – a chronic disorder of the mental processes caused by a brain disease, marked by disorders of personality and impaired reasoning… There’s no cure …. He may not have more than a year…” Nula is left numb with shock.

Although reluctant to accept the consultant’s brutally delivered diagnosis, Nula realises how important it is to make the most of whatever time she still has with her husband – while he still has at least some of his faculties. Over the next five years she becomes James’s carer, nurse and mother. “My role as wife and lover has to be surrendered, and is gone forever. Instead, I become embroiled in a marathon battle with the bastard dementia, determined to hold on to every second of our life together. I include James in everything I do, for as long as possible, wanting to share and give him lovely, last experiences while he still has a window. So I carry on doing things normally, taking him to the cinema, the theatre, the opera and to concerts. Order his favourite food in restaurants and we drink the best wine.”

Sadly but inevitably, though, James’s dementia gradually worsens and it becomes impossible for Nula to care for him at home. She eventually finds a home specialising in dementia not far from London and, with a heavy heart, she entrusts James to their expert care. James settles in well at the home, but it is Nula who finds the change traumatic. Although she realises that getting her husband into residential care is the kindest and most sensible option, she is nevertheless wracked with guilt and finds the first few weeks of living on her own at home without her husband of many years extremely difficult and painful.

After she has been visiting James almost daily for several months, the manager of the home phones to say she is arranging a lunch for family members to enable them to get to know each other and share their experiences. It is at this lunch that Nula meets the husband of another resident, who is as devastated and guilt-ridden about his wife’s condition as Nula is about James. Whereas most of the guests are the sons and daughters of residents, John Suchet (the author of My Bonnie – My Bonnie by John Suchet | Waterstones) and Nula Knight are almost the only people with a partner in the home. Coming from a similar background and with both having a relatively young partner who has been cruelly robbed of their mental faculties through dementia, they find they have a huge amount in common. When John shares with Nula his profound sense of loss and heartbreak at the way dementia has stolen his beloved Bonnie from him, Nula writes: “It is as if a light has been switched on in my soul.” After much heart-searching they both realise that their partners’ dementia has put them in an awful place and that they simply have to make a new life for themselves: “It was our only way to get through the pain.”

The rest of the book covers their tentative steps to forge a new life together, while witnessing the slow and painful decline of their respective spouses. As James’s dementia steadily worsens, Nula spends days and nights at his bedside, but sadly it is just when she has gone back home to get a proper night’s sleep that that she receives a phone call from the home to say that James has passed away. John’s wife, Bonnie, dies a few months later, yet Nula admits to being hit by “an overwhelming tsunami of sadness”, which she struggles to come to terms with, despite the knowledge that: “It is all over. James and Bonnie are free.”

Nula’s overwhelming grief and agony at her loss makes her decide to stop seeing John. He doggedly keeps in touch with her by email and after a few months they meet up again in London. Nula immediately realises how deep her feelings are for John and they get back together again.

So, in the end, this profoundly sad story has a happy ending, Nula writes in such a way that the reader feels deeply involved in her story. We share her sadness and despair at the way dementia takes away her husband, James, the light of her life, but we also share in her joy at finally being able to find happiness again after so many years of grief and heartache. For Nula and John, at least, there is light at the end of the tunnel.

As well as offering a moving depiction of Nula’s long and painful descent from total happiness into profound despair and then slowly back towards a more mellow and nuanced state of happiness, this book gives the reader a clear idea of what they can expect – and how best to cope – if their loved one should develop Pick’s Disease, or, indeed, any other form of dementia. Click Contact Chesterford Homecare if you want a free care quote.